By Elizabeth Quinn

Here’s a trap that we (adults) fall into too often when we are thinking with children about how the physical world works: we think that it is our job to make sure that the children arrive at the “correct” answer. As a result, we find ourselves pulled out of the role of collaborator, thinking and investigating together with a child, and into the role of explainer, telling the child what to think. Children may gain some scientific information from such an interaction, but they lose the far more important opportunity to practice thinking scientifically, to discover relationships and connections for themselves, and to experience the joy of figuring things out. Here are some ideas for staying out of this trap:

First, remind yourself of the way that adult scientists approach knowledge. Scientists do not gain new understandings about the world by accepting ‘because I said so’ explanations. They advance knowledge by collaborating and studying the work of other scientists, but also by questioning what they know, by clarifying and defining the unanswered questions, and by investigating for evidence to help them answer those questions. To a scientist, the ‘correct answer’ means the explanation that best fits the evidence we have right now… and that answer is constantly evolving as we collect more evidence.

As you think together with children about scientific questions, try to focus on helping them think like scientists. That means aiming, not for a ‘final answer,’ but for an answer that makes sense based on what the child knows right now and what they can observe or investigate. As children grow, their answers will evolve along with their thinking and, as they come to know and understand more, will move closer to accepted scientific explanations.

For example, a four-year-old thinking about why the sky is blue will probably not come up with the interaction of light and atmospheric particles as an answer. Instead, they might decide that it is blue because that is the sun’s favorite color, or because the sun took all the orange and left only the blue. Don’t think of that as a failure! Just by asking the question and beginning to generate theories, they have created a mental model which includes the sky, the sun and themselves as the watcher. As they grow and have more experience with light, they can refine that mental model, replacing the sun who has color preferences with a sun which is a source of all colors of light and imagining the journey that light takes through the atmosphere to get to their eyes.

Your job is not to get them to that answer today… it is just to spend time engaging in that kind of thinking with them. Ask questions that aid the child to take the next step in their thinking, not ones that point the way to a pre-determined answer.

Second, remember the value of dialogue for children’s learning. If you fall into the ‘correct answer’ trap, you put the experience of collaboration at risk as you become an explainer rather than a co-thinker. To help yourself stay out of the trap, remember how important that experience is for children!

By collaborating with you to think about their question (rather than listening to you tell them the answer), children learn and grow in so many ways. They strengthen their listening skills and their skills for expressing their ideas using both language and other means of representation such as drawing. They build a sense of pride in being treated as an equal partner in your collaboration. They get a chance to ‘borrow’ your adult thinking skills and routines as you model your own thinking about the question you are focusing on. And they experience the back-and-forth interaction of collaboration itself, a key skill for school, life and work.

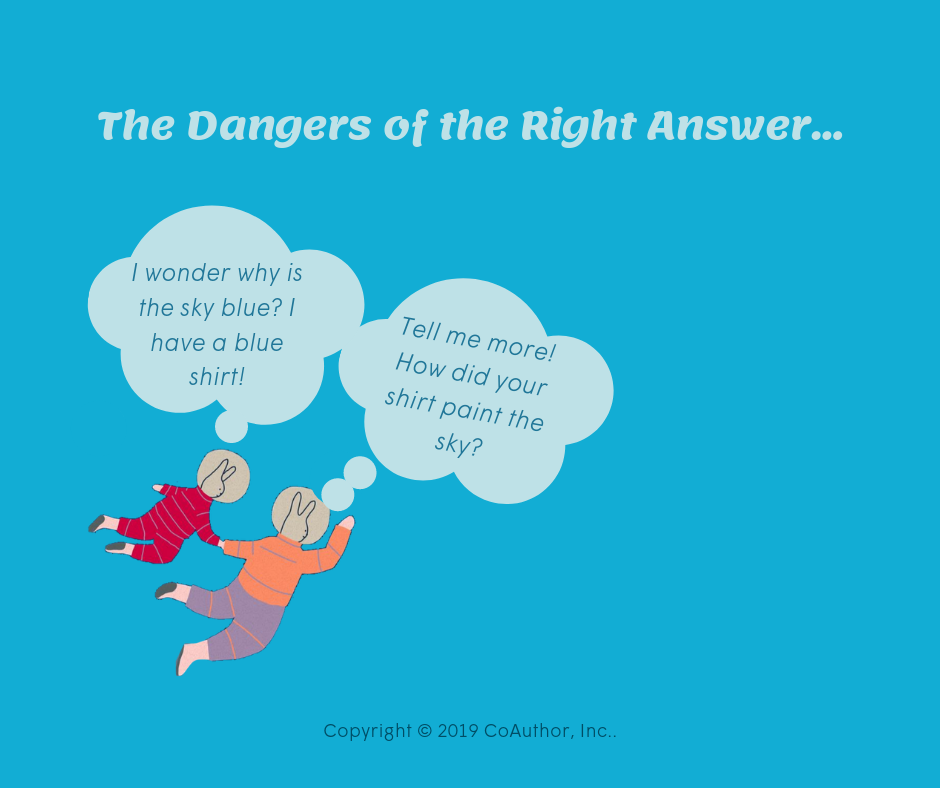

Third, change your lens. As you get ready to start thinking about a scientific question with a child, take a moment to remind yourself of your goal. If you catch yourself thinking “My goal is to get this child to understand X,” stop and reframe! My suggestion: try “My goal is to understand as much as possible about how this child is thinking about X.” This goal will lead you to ask meaningful questions which will support the child in refining and explaining their thinking. For example, if the question is about why the sky is blue, and the child says “My shirt is blue,” ask them how their shirt colored the sky. Then listen to their answer and ask another question.

In order to answer your questions, the child will be pushed to identify relevant evidence and to evaluate the connections between that evidence and the explanation they are proposing. Over time, by working to understand the child’s thinking you will be helping them grow their ability to think.

That way, when they eventually grasp the ‘correct’ answer, they will understand how scientists arrived at that answer in the first place… and they will be ready to ask the next question.

If you would like to practice this method of co-thinking with your child/students about different topics, try out our free app CoAuthor.

Elizabeth Quinn is a child and teacher educator, author, and co-creator of CoAuthor.